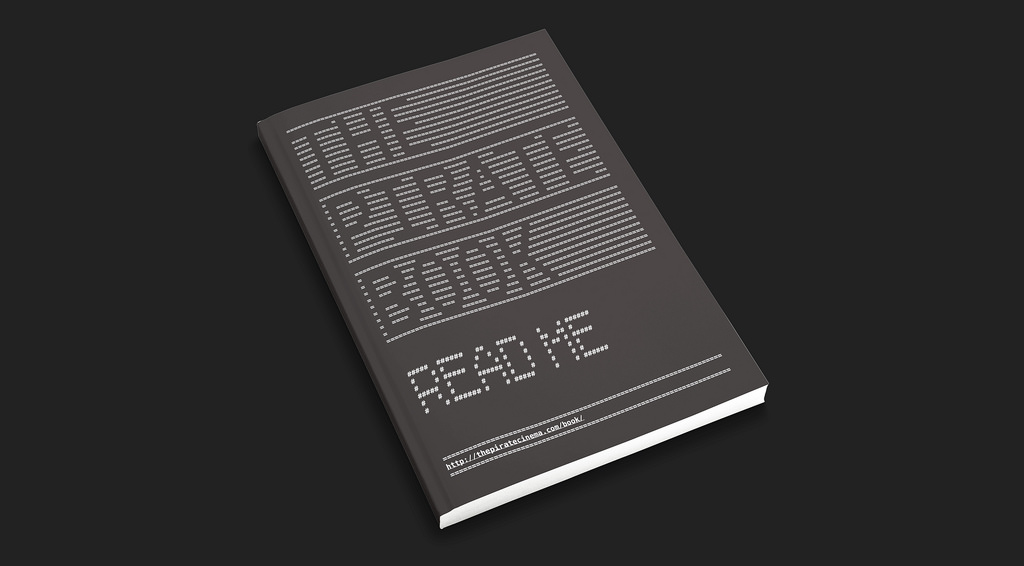

The Pirate Book, A compilation of stories about sharing, distributing, and experiencing cultural content outside the boundaries of local economies, politics, or laws. By Nicolas Maigret and Maria Roszkowska.

Despite being the nation that ostensibly spearheads the war on piracy, the United States was at its inception a “pirate nation” given its refusal to observe the rights of foreign authors. In the absence of international copyright treaties, the first American governments actively encouraged the piracy of the classics of British literature in order to promote literacy. The grievances of authors such as Charles Dickens fell upon deaf ears, that is until American literature itself came into its own and authors such as Mark Twain convinced the government to reinforce copyright legislation.

The paragraph above is copy/pasted from the book. It is symptomatic of a publication that informs, challenges any bias and assumptions you might have about piracy and does so with wit and intelligence. It also shows the spirit of The Pirate Book, a work more concerned with contemporary cultural practices around the world than with the legal subtleties of copyright infringement.

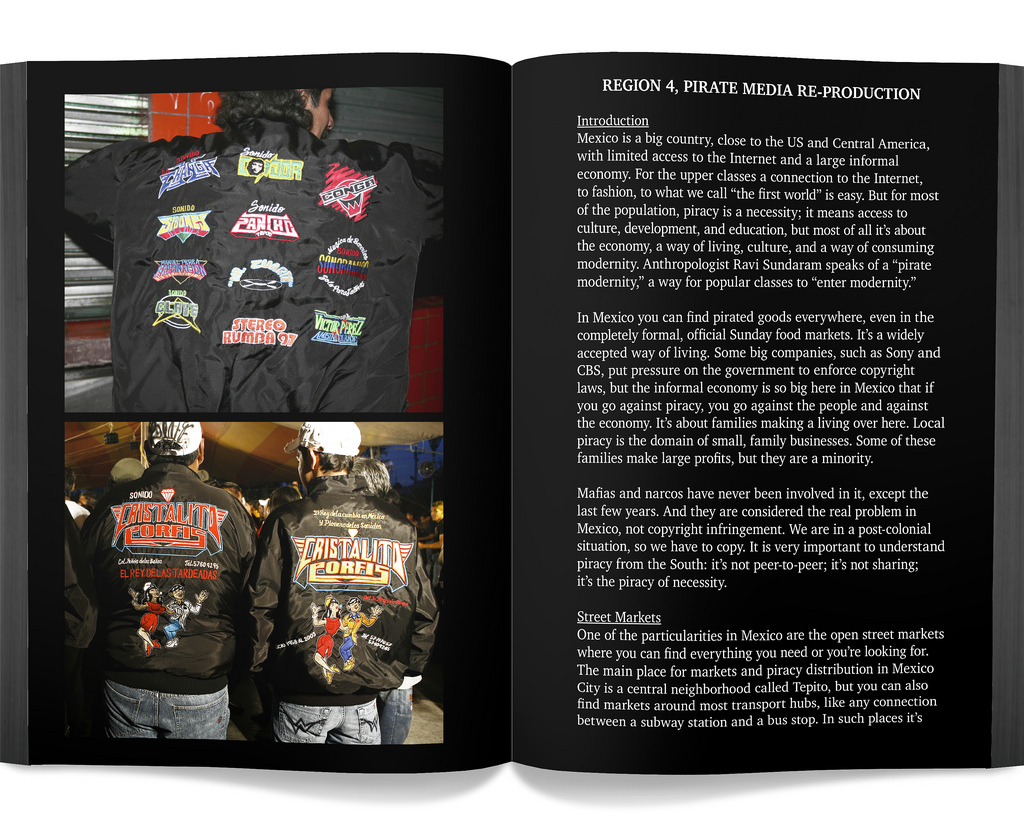

Sonidero in Mexico City

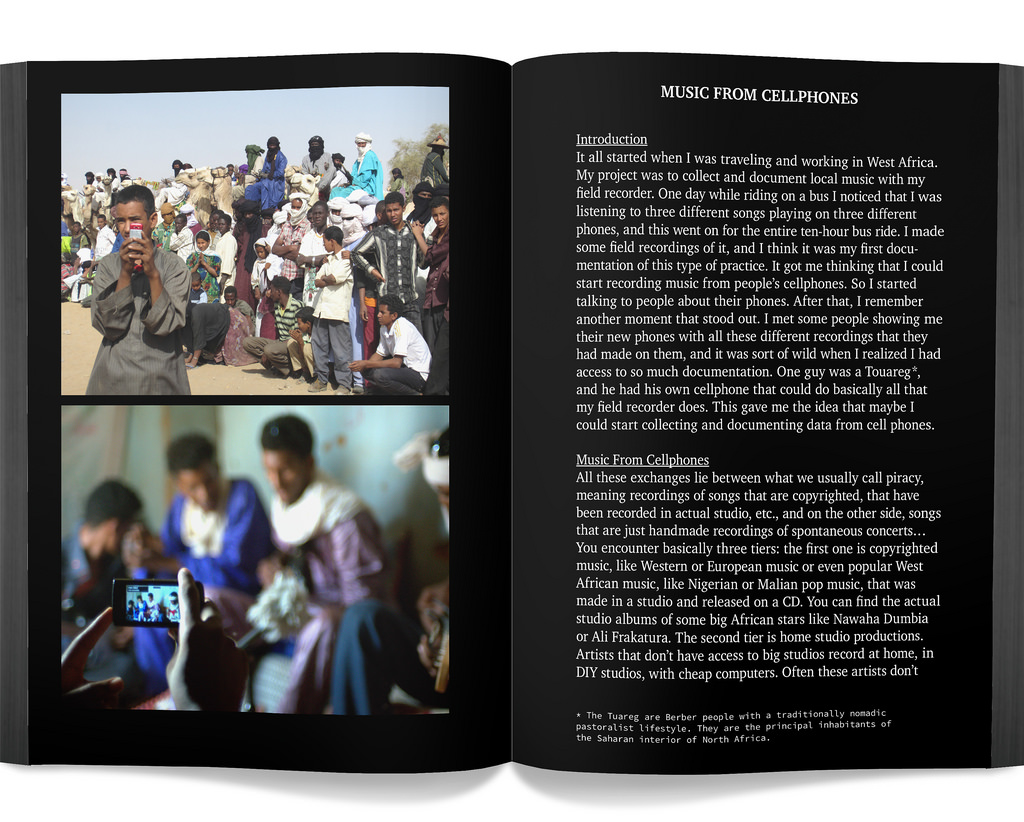

Music distribution from mobile phone to mobile phone in West Africa

The pirate book is an impeccably curated collection of essays and photos by artists, researchers, militants and bootleggers who share their experiences and anecdotes of piracy and anti-piracy practices through history and across cultures.

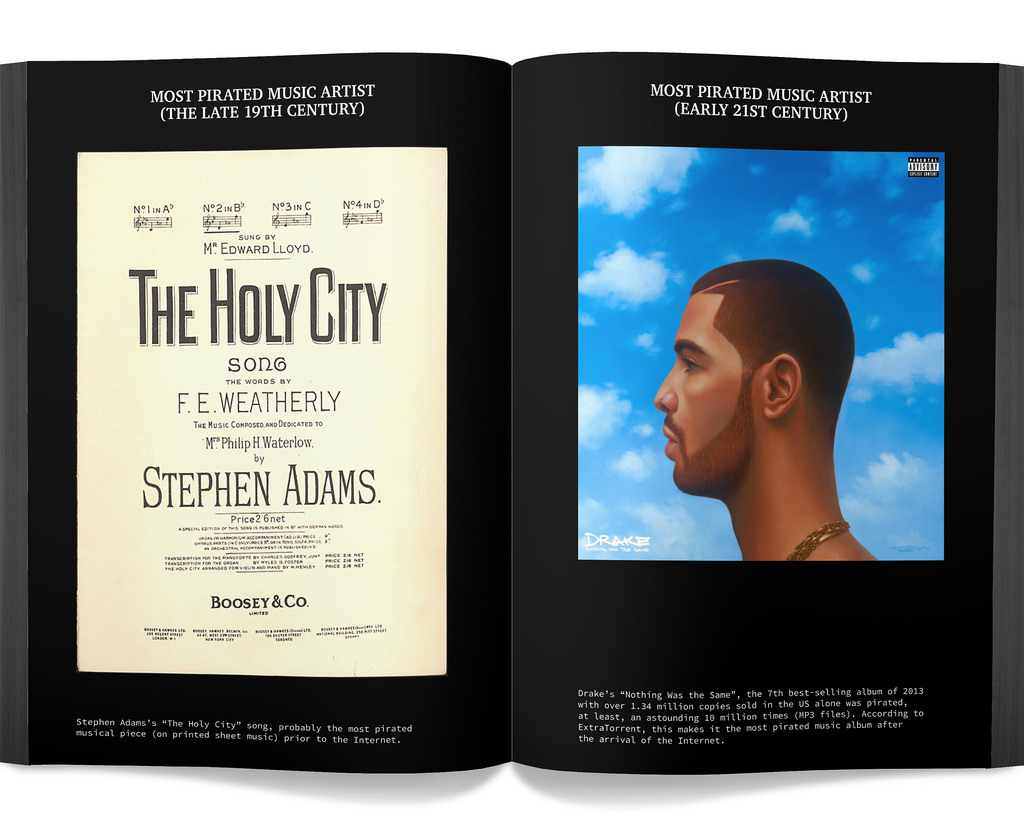

The first part of the book, the Historical Perspective, brings side by side key moments of the history of piracy with their contemporary counterpart. I’m not going to list them all (you can quickly check them for yourself as the book is both print on demand and free download) but here is just one example:

Above: Pirate Bus in Regent’s Park, during the General Strike, 1926

In London, independent bus operators appeared in the mid of 19th century, following the tourism boom that accompanied the Great Exhibition of 1851. Their vehicles were soon popularly termed

“pirate” buses

The contemporary correspondent of the London buses are the Google private shuttle buses, viewed as symptoms of the ruthless gentrification of San Francisco driven by the tech sector. Activists also denounced the unpaid use of public bus stops by private companies, which leads to delays and traffic congestion.

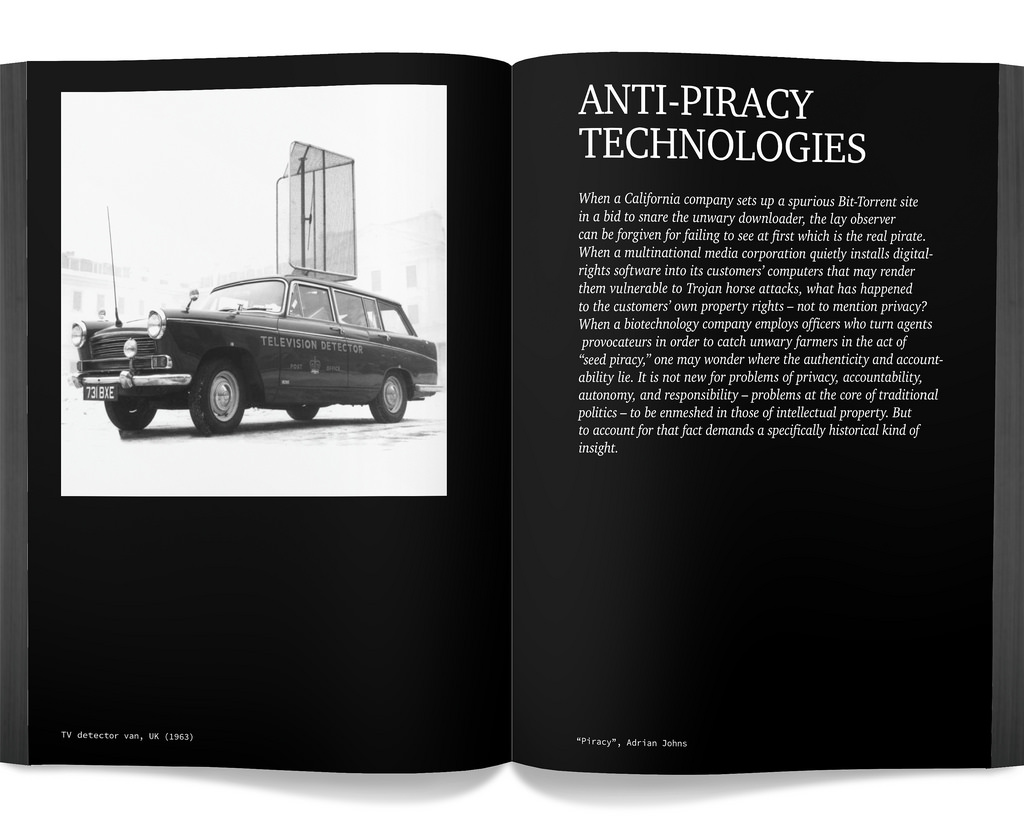

TV detector van, UK, 1963

Another entertaining chapter lists the strategies that cultural industries have adopted in their fight against piracy: educational flyers, hologram stickers, game alterations, false TV signal detectors (vehicles equipped with very conspicuous antenna that were supposed to be able to detect which households had not paid their TV licence), torrent poisoning, etc. I’m quite fond of the rather baroque way the publishers of the game Leisure Suit Larry Goes Looking for Love (in Several Wrong Places) adopted to protect the copies from piracy:

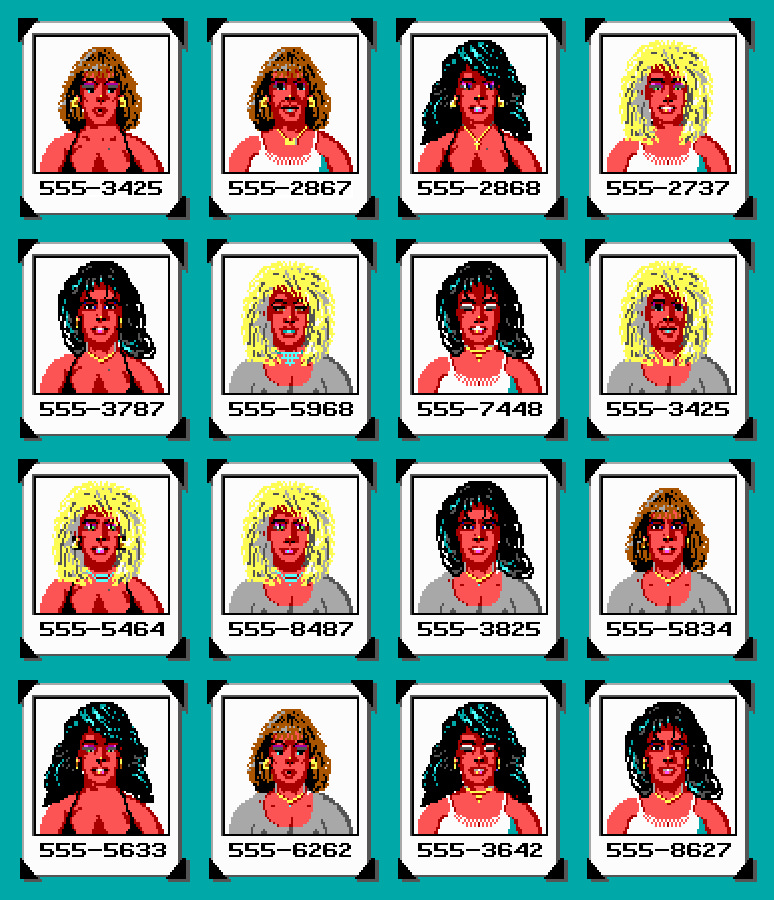

Leisure Suit Larry Goes Looking for Love (in Several Wrong Places), 1988

In order to be able to launch the game, players were required to posses a physical copy of the instruction manual. When the game started up, it presented the player with a photo of a random woman. The player had then to look through the physical instruction manual, match her image with a telephone number and input it into the game.

I found the last part of the book particularly compelling. It counts a series of essays that explore local practices of piracy in Brazil, Cuba, Mexico, China, India, and Mali and other countries where piracy is the only affordable way for many people to access culture, entertainment and education. The stories i was less familiar with came from Mexico City and from a city in India called Malegaon:

El Paquete hard drive, a pouch that protects the disc and a USB cable

Cuba’s isolation by the US embargo made audio-visual piracy vital not only for citizens but also for the government itself who needed content for its official television channels as well as books and academic publications for universities. Most Cubans don’t have access to internet and when they do it is neither fast nor safe from governmental scrutiny. But what they do have is El Paquete Semanal, a terabyte of music, movies, soap operas, mobile phone apps and even a classifieds section similar to Craigslist. Every week, unidentified curators compile a selection of content which subscribers upload on a hard drive that can be plugged directly into a TV.

Supermen of Malegaon, the documentary, 2008

In India, the city of Malegaon has built a parallel cinema industry that creates spoof movies of Bollywood blockbusters. These cheaply shot and edited films echo their own local context and rely on an infrastructure enabled by media piracy and the proliferation of video rentals.

The final chapter, written from Ernesto Van Der Sar founder of TorrentFreak.com, argues through an analysis of music and film sales that the music industry is doing better than ever before but systematically blames piracy as soon as a new film or record doesn’t sell well.

That’s it! A quick and very incomplete overview of The Pirate Book. I’d recommend that book to anyone who can’t make up their mind about piracy, to your mother who thinks pirates are a bunch of ruffians who prevent Celine Dion from making a living, and to anyone who’s simply interested in contemporary popular culture and in non-western perspectives on DIY and inventiveness.

Views inside the book:

The book is an extension of Maigret’s installation and performance The Pirate Cinema, A Cinematic Collage Generated by P2P Users which uncovers in real time the hidden activity and the geography of peer-to-peer file sharing but also the aesthetic dimension of P2P architectures.

As befits the theme of the book, the authors invite readers to copy the texts of this book and do with them as he/she pleases.

The Pirate Book was published by Aksioma – Institute for Contemporary Art, Ljubljana Co-published by Pavillon Vendôme Art Center, Clichy.

Produced by Aksioma, Pavillon Vendôme, Kunsthal Aarhus and Abandon Normal Devices.